Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Treatment options:

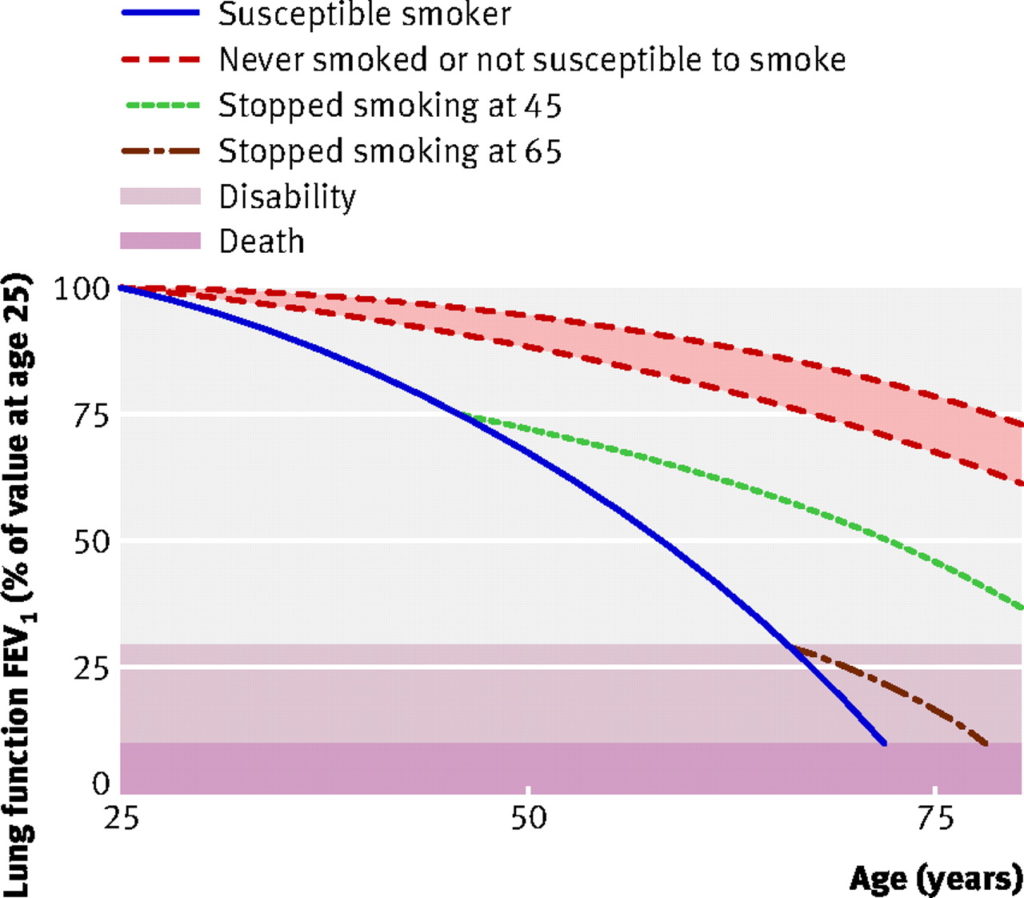

For smokers with COPD, continued smoking reduces lung capacity (FEV1) by an average of 62ml per year1.

For those who manage to stop smoking, their lung capacity will immediately begin to stabilise.

- Successful quitters’ lung capacity then just gradually reduces with age, at the same rate as lifelong non-smokers (32ml per year)1.

This graph shows changes in lung function over time in continuing smokers compared to quitters:

|

|

note: ‘susceptible’ and ‘non-susceptible’ differentiate those smokers who will or will not develop pathological changes of COPD in response to smoking (i.e. some people get away with it).

When GPs told smokers their FEV1 results in terms of “lung age” (as opposed to litres), they were more likely to quit. Quit rates were 13.6% compared to 6.4% in a high-quality randomised study in UK general practice2.

Lung age calculators can be found online or can be estimated approximately using the graph above.

References

1)Lee P, Fry J. Systematic review of the evidence relating FEV1 decline to giving up smoking. BMC Med 2010; 8: 84

2) Effect on smoking quit rate of telling patients their lung age: the Step2quit randomised controlled trial.

Pulmonary rehabilitation programmes improve exercise tolerance and quality of life (QoL) in people with COPD.

The effect is greater than that seen with inhaler therapies.

| Improvement in CRQ QoL score | +0.79 | CRQ is a respiratory disease specific, validated, QoL score which measures from 0-7 across domains including dyspnoea, fatigue, emotional function and mastery (sense of control).

More than +0.5 is likely to be a noticeable improvement. |

| – | ||

| Improvement in 6-minute walking distance | +44 metres | This is under test conditions, walking on the flat at whatever speed is comfortable, and being allowed to stop as needed. |

Evidence Source: Cochrane

Figures derived from a 2015 Cochrane review1:

- 28 RCTs involving 1879 people

- comparing pulmonary rehabilitation with usual care

- pulmonary rehabilitation was defined as exercise training for at least four weeks with or without education and/or psychological support

- inpatient and outpatient programmes were included

Reference

1)McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003793

Evidence Quality: MODERATE - VERY LOW

Cochrane rated the evidence for improvement in quality of life as MODERATE quality.

| This research provides a good indication of the treatment effect.

There is a moderate possibility that the true effect is smaller or greater. |

- RCTs at low risk of bias

- statistically significant results with reasonable confidence intervals

However,

- some variation in the size of effect seen between trials

Cochrane rated the evidence for improvement in walking distance as VERY LOW quality.

| This research does not provide a reliable indication of the treatment effect.

There is a very high possibility that the true effect is greater or smaller. |

- some risk of bias in RCTs

- possible publication bias

- some variation in the size of effect seen between trials

Reference

1)McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003793

Study Population

The Cochrane review reported that, for the 38 studies:

- 31% female participants

- median duration of study 45 days

- other demographic and clinical characteristics not summarised

- 2/3 hospital based, 1/3 community-based rehabilitation programmes

Reference

1)McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003793

A significant minority of patients with COPD will have pre-existing asthma, or have an element of steroid-responsiveness to their airway obstruction.

Those with asthmatic features, or features of steroid responsiveness, may benefit from a different approach to inhaler therapies (see the “Inhaled therapies” section below).

There are no clear distinctive features to define this group. NICE suggest the following as a guide:

|

Clinical features differentiating COPD and asthma |

COPD | Asthma |

|---|---|---|

| Smoker or ex-smoker | Nearly all | Possibly |

| Symptoms under age 35 | Rare | Often |

| Chronic productive cough | Common | Uncommon |

| Breathlessness | Persistent and progressive | Variable |

| Night time waking with breathlessness and/or wheeze | Uncommon | Common |

| Significant diurnal or day-to-day variability of symptoms | Uncommon | Common |

Additional features which may help identify asthma or steroid responsiveness:

*NICE does not suggest a threshold eosinophil count. GOLD guidelines suggest an eosinophil count of 0.1 x 109/L (<100 cells/uL) as a level below which patients are unlikely to benefit from inhaled corticosteroids2. A UK primary care study3 suggested a threshold of 0.15 x 109/L (150 cells/uL). |

||

The NICE guideline contains more detail about diagnostic criteria and strategies for COPD.

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. [London]: NICE; 2018. (NICE guideline [NG115])

2) GOLD report: 2022 update. Lancet Respir Med 2022 Feb; 10(2): e20

3),, et al. Blood eosinophils to guide inhaled maintenance therapy in a primary care COPD population. Jan;

The place of different types of inhaled therapies in the treatment of COPD will vary from person to person, in terms of

- whether they have features of asthma or steroid responsiveness,

- their symptomatic response, and

- what the goal of treatment is – to improve symptoms and/or prevent exacerbations?

This is complicated stuff, you may want to grab a cup of coffee 🙂 We’ve tried to make this as simple as possible, but it takes some digesting.

In the main graphics we show the average comparative benefits of these inhaled therapies in RCTs.

Regarding which inhaler and when, NICE suggests two strategies.

- These are intended to be adjusted to an individual’s priorities and response to treatment.

First, think about which of these two categories your patient falls into:

Strategy for patients with no features suggesting asthma or steroid responsiveness

Strategy for patients with features suggesting asthma or steroid responsiveness

Patients with COPD who took an inhaled LABA (salmeterol) had an increase in FEV1 of 51mls compared to those taking placebo inhaler

If 100 people with COPD take a LABA (salmeterol), 7.5 fewer will have an exacerbation over 6 months compared to those who took a placebo inhaler

No difference in quality of life measures or exercise tolerance were seen in these studies comparing LABA with placebo inhaler

Patients with COPD who took an inhaled LAMA (tiotropium) had an increase in FEV1 of 30mls compared to those taking placebo inhaler

If 100 people with COPD take a LAMA (tiotropium), 7.5 fewer will have an exacerbation over 6 months compared to those who took a placebo inhaler

If 100 people with COPD take a LAMA (tiotropium), 7.5 fewer will have a hospitalisation for COPD over 6 months compared to those who took a placebo inhaler

A small, statistically significant improvement in quality of life score was seen with tiotropium compared to placebo inhaler, but the size of the change was unlikely to represent a meaningful difference

Changes in FEV1 were not reported in the studies comparing these treatments

If 100 people with COPD take a LABA+LAMA combination, 3.3 fewer will have an exacerbation of COPD over 6 months compared to those who took a LABA alone

A small, statistically significant improvement in quality of life score was seen with LABA+LAMA compared to LABA alone, but the size of the change was unlikely to represent a meaningful difference

Patients with COPD who took a combined triple therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA+ICS) had an increase in FEV1 of 54mls compared to those taking a combined double therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA)

If 100 patients with COPD take a combined triple therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA+ICS), 3 fewer will have an exacerbation over 1 year compared to those who take a combined double therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA)

Patients with COPD who took a combined triple therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA+ICS) had an average of 0.91 exacerbations per year compared to an average of 1.21 exacerbations per year in those taking a combined double therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA)

A small, statistically significant improvement in quality of life score was seen with triple therapy compared to double therapy, but the size of the change was unlikely to represent a meaningful difference

If 100 patients with COPD take a combined triple therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA+ICS), 3 more will develop pneumonia over 1 year compared to those who take a combined double therapy inhaler (LABA+LAMA)

Evidence Source: Cochrane/NICE

Placebo v LABA

Figures derived from a 2006 Cochrane Review1:

- 7 RCTs involving 2026 people

- placebo inhalers v LABA inhalers (mostly salmeterol)

Placebo v LAMA

Figures derived from a 2005 Cochrane Review2:

- 12 RCTs involving 6584 people

- placebo inhalers v LAMA inhalers (mostly tiotropium)

LAMA v LABA+LAMA

Figures derived from a 2018 Cochrane Review3:

- 5 RCTs involving 2488 people

- LAMA therapy was either alclidinium or tiotropium

LABA+LAMA v LABA+LAMA+ICS

Figures derived from a single trial4 within a 2018 NICE evidence review5:

- involved 10,335 people

- compared once-daily Ellipta inhaler of triple therapy (fluticasone furoate 100mcg+umeclidinium 62.5mcg+vilanterol 25mcg) to once-daily Ellipta inhaler of double therapy (umeclidinium 62.5mcg+vilanterol 25mcg)

- this single trial is presented as it is the largest of the 3 trials in the NICE review, and the only one to run for a whole year

References

1)Appleton S, Poole P, Smith BJ et al. Long‐acting beta2‐agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001104

2)Barr RG, Bourbeau J, Camargo Jr CA. Tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002876

3)Oba Y, Keeney E, Ghatehorde N, Dias S. Dual combination therapy versus long‐acting bronchodilators alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD012620

4)Lipson D, Barnhart D, Brealey N et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1671-1680

5)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Evidence review: Inhaled triple therapy.[Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2018. (NICE guideline [115])

Evidence Quality: MODERATE

Cochrane and NICE rated the majority of this evidence as MODERATE quality1-5.

- randomised controlled trials at low risk of bias

- statistically significant, mostly consistent results

However,

- effect sizes were often small, with wide confidence intervals

The evidence for placebo v LAMA therapy was rated as HIGH quality, as

- the effect size was larger, with reasonable confidence intervals.

References

1)Appleton S, Poole P, Smith BJ et al. Long‐acting beta2‐agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001104

2)Barr RG, Bourbeau J, Camargo Jr CA. Tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002876

3)Oba Y, Keeney E, Ghatehorde N, Dias S. Dual combination therapy versus long‐acting bronchodilators alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD012620

4)Lipson D, Barnhart D, Brealey N et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1671-1680

5)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Evidence review: Inhaled triple therapy.[Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2018. (NICE guideline [115])

Study Populations

The population characteristics in the trials for LABA and LAMA inhalers1-3 can be summarised as:

- mean age mid-60s

- 1/4 female

- ethnicity poorly reported

- ex or current smokers

- moderate to severe COPD (FEV1 averages in mid-40s% of predicted)

- low levels of reversibility to salbutamol, approx 10%

- significant co-morbidities were often in the exclusion criteria

The population characteristics of the IMPACT study4 of triple therapy (LABA+LAMA+ICS) were:

- mean age 65

- 34% female

- ethnicity: White 78%, Japanese/SE Asian 16%, Native American 2%, Black 2%

- COPD duration in years <1: 5%, 1-5: 33%, 6-10: 33%, 11-15: 18%, >15: 12%

- moderate or severe COPD exacerbations in previous year 1: 45%, 2: 44%, ≥3: 11%

- mean FEV1 46% predicted (post-bronchodilator)

- 1/3 current smokers, 2/3 ex-smokers

- co-morbidities not reported, significant other lung disease was an exclusion criterion

References

1)Appleton S, Poole P, Smith BJ et al. Long‐acting beta2‐agonists for poorly reversible chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001104

2)Barr RG, Bourbeau J, Camargo Jr CA. Tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002876

3)Oba Y, Keeney E, Ghatehorde N, Dias S. Dual combination therapy versus long‐acting bronchodilators alone for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD012620

4)Lipson D, Barnhart D, Brealey N et al. Once-Daily Single-Inhaler Triple versus Dual Therapy in Patients with COPD. N Engl J Med 2018; 378: 1671-1680

LABA inhalers

Headache, palpitations, tremor

1 in 10 – 100 people

Source: BNF

LAMA inhalers

Antimuscarinic side effects

1 in 10 – 100 people

- e.g., constipation, cough, dizziness, dry mouth, headache, nausea

Source: BNF

Cardiovascular safety of tiotropium

Tiotropium via Respimat or HandiHaler device is now thought not to be associated with cardiovascular risk, though the MHRA suggests some caution in groups at very high cardiovascular risk.

more

In the 2000s, concern developed regarding excess cardiovascular death in patients using tiotropium Respimat devices seen in some analyses of clinical trials. This evidence was never conclusive, though a proposed mechanism was the rapid delivery of the drug causing an antimuscarinic effect on cardiac tissue.

A large trial published in 2015:

- involved 17,135 patients over 2.3 years

- compared tiotropium delivered by HandiHaler or Respimat devices

- found no difference in cardiovascular or total mortality between the two1

The MHRA now suggests avoiding tiotropium only in particular groups (who were excluded from this last trial):

‘When using tiotropium delivered via Respimat or HandiHaler to treat chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD):

- take the risk of cardiovascular side effects into account for patients with conditions that may be affected by the anticholinergic action of tiotropium, including:

- myocardial infarction in the last 6 months

- unstable or life threatening cardiac arrhythmia

- cardiac arrhythmia requiring intervention or a change in drug therapy in the past year

- hospitalisation for heart failure (NYHA Class III or IV) within the past year

- tell these patients to report any worsening of cardiac symptoms after starting tiotropium; patients with these conditions were excluded from clinical trials of tiotropium, including TIOSPIR

- review the treatment of all patients already taking tiotropium as part of the comprehensive management plan to ensure that it remains appropriate for them; regularly review treatment of patients at high risk of cardiovascular events

- remind patients not to exceed the recommended once daily dose

- continue to report suspected side effects to tiotropium or any other medicine on a Yellow Card.’

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

Oral candidiasis, taste altered, voice alteration

1 in 10 – 100 people

Source: BNF

Pneumonia

Up to 1 in 23 people with COPD develop pneumonia over 18 months as a result of ICS.

Rates are higher with fluticasone than budesonide, and vary according to baseline risk.

more

A 2014 Cochrane review3 found the following rates of pneumonia in RCTs:

| Placebo group | Inhaled Steroid | Number Needed to Harm | Relative Risk Increase | |

| Fluticasone containing inhaler | ||||

| All pneumonia | 7.2% | 11.6% | 23 | x 1.6 |

| Pneumonia needing hospitalisation | 2.5% | 4.3% | 56 | x 1.7 |

| Budesonide containing inhaler | ||||

| All pneumonia | 2.8% | 3.1% | 333 | x 1.1 |

| Pneumonia needing hospitalisation | 0.9% | 1.5% | 167 | x 1.7 |

No difference was seen in mortality due to pneumonia or all-cause mortality.

Note: the Number Needed to Harm is much higher in the budesonide trials. This is mainly due to a lower baseline risk of pneumonia in the budesonide study populations. The relative risks of budesonide and fluticasone are more closely matched.

MODERATE quality evidence

Fractures

1 in 333 people (approximately) with COPD sustain a fracture over 18 months as a result of ICS.

more

Systemic absorption of corticosteroids can reduce bone density.

A 2011 meta-analysis reviewed 16 RCTs involving 15,513 patients comparing ICS to placebo over an average of 18 months:

| Placebo | ICS | Number Needed to Harm | Relative Risk Increase | |

| Any fracture | 1.7% | 2% | 333 | x 1.2 |

LOW quality evidence:

- large RCTs, but main result only just statistically significant, and some uncertainty in reporting of results in some trials

Adrenal suppression

ICS have been shown to suppress adrenal function in physiological studies, though the absolute risk of acute adrenal crisis due to ICS is unknown and probably very low.

more

Physiological studies have shown suppression of adrenal function with increasing doses of ICS4. These form the basis of recommendations to provide patients with steroid emergency cards.

Dosage thresholds to provide steroid emergency cards are recommended in the BNF:

- beclomethasone >1000mcg/day or equivalent

- fluticasone >500mcg/day or equivalent

The BNF lists adrenal suppression as a “rare or very rare” side effect (1 in 1000 to <1 in 10,000)

References

1)Wise R, Anzuetto A, Cotton D et al. Tiotropium Respimat Inhaler and the Risk of Death in COPD. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 1491-1501

2)MHRA. Tiotropium delivered via Respimat compared with Handihaler: no significant difference in mortality in TIOSPIR trial. 2015. Accessed online 4/1/23

3)Kew KM, Seniukovich A. Inhaled steroids and risk of pneumonia for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD010115

4)Lipworth BJ. Systemic Adverse Effects of Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159(9): 941–955

Key

People who have an adverse event

People whose adverse event is prevented by treatment

People who were never going to have an adverse event anyway

Graphics and NNTs are rounded to the nearest integer

Stats explained

These three statistical terms offer three different ways of looking at the results of trial data.

ARR

Absolute Risk Reduction

This tells you how many people out of 100 who take a treatment have an adverse event prevented.

MoreThe value of the ARR changes with the baseline risk of the person (or population) taking the treatment. The higher the starting risk, the greater the absolute chance of benefit.

You need to think about over what time the trial data show this benefit, as it is usually assumed that more absolute risk reduction is gained over time.

Your patient might be taking the treatment for much longer than the length of a clinical trial (or, if life expectancy is limited, perhaps for less time).

NNT

Number Needed to Treat

This tells you how many people need to take the treatment in order for one person to avoid an adverse event.

The lower the number, the more effective the treatment.

MoreThe value of the NNT changes with the baseline risk of the person (or population) taking the treatment. The higher the starting risk, the smaller the NNT.

You need to think about over what time the trial data show benefit, as it is usually assumed that more benefit is gained over time and therefore the NNT will drop over time.

Your patient might be taking the treatment for much longer than the length of a clinical trial (or, if life expectancy is limited, perhaps for less time).

RRR

Relative Risk Reduction

This tells you the proportion of adverse events that are avoided if the entire population at risk is treated.

MoreThe value of the RRR is usually constant in people (or populations) at varying degrees of risk.

It is also usually assumed to stay constant over time.

This can be helpful, especially when thinking about population outcomes, but can be misleading for an individual person:

For example, a RRR of 25% in someone with a baseline risk of 40% would give them an ARR of 10% and an NNT of 10.

A RRR of 25% in someone with a baseline risk of 4% would give them an ARR or 1% and an NNT of 100.