Gout

Gout is common and often a source of recurrent pain and disability.

Preventive treatments, if used well, can dramatically reduce symptoms for most people.

The available evidence is limited.

It is not known whether those patients with a first attack or with infrequent flares might benefit from long term treatments.

Treatment options:

NICE recommends offering one of these 3 options to manage an acute flare of gout, taking into account the person’s comorbidities, co–prescriptions and preferences.

- NSAID, or

- colchicine, or

- corticosteroid

Evidence is limited, but all three treatments seem to be equivalent at reducing pain and joint swelling. They have slightly different side effect profiles, summarised in the table below.

Corticosteroids appear to have the fewest side effects:

- studies are small and unlikely to fully predict the risk of side effects in vulnerable patients

Ice packs may be a helpful adjunct – see button below.

| Outcome | Evidence Quality | ||

| Placebo* | NSAID | ||

| Reduction in pain score by ≥50% at 24 hours | 27% | 73% | LOW (1 trial, 30 patients) |

| Placebo* | Colchicine | ||

| Reduction in pain score by ≥50% at 2 weeks | 17% | 42% | MODERATE (1 trial, 132 patients) |

| NSAID# | Colchicine | ||

| Pain score at 2 weeks | 1.02 | 0.96 | HIGH (no clinical difference) |

| Diarrhoea | 14% | 31% | HIGH |

| NSAID# | Corticosteroid | ||

| Patients with clinically significant pain reduction at 2 weeks | 53% | 49% | MODERATE (n/s difference) |

| Abdominal pain within 2 weeks | 13% | 7% | MODERATE |

| Vomiting | 5.5% | 0.4% | HIGH |

* Neither of the placebo trials were big enough to deliver information on side effect rates

# NSAID trials were not large enough to show risk of severe upper GI side effects (ulcers, bleeds)

Evidence Source: NICE

Figures from the evidence summary for the 2022 NICE guideline1, except for NSAIDs v placebo, which is taken from a 2021 Cochrane review2.

There are only two RCTs of treatments against placebo, both of which are small and offer limited evidence.

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

2)van Durme CMPG, Wechalekar MD, Landewé RBM et al. Non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for acute gout. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD010120

Ice packs

A small study1 in NICE’s evidence review2 suggested that ice packs applied to inflamed joints during a flare of gout may provide meaningful extra pain relief:

- included 19 patients with an acute gout flare

- ankle, knee or MTP joint flares

- all patients took oral corticosteroids and colchicine

- randomised to ice pack+drugs or drugs alone

- the ice pack was tied on for 4 x 30 minutes every 24 hours

- from a US rheumatology service

Results:

| Drugs alone | Drugs+ice packs | |

| VAS* pain score at entry | 9.6 | 8.6 |

| VAS* pain score at 1 week | 4.7 | 0.8 |

*Visual Analogue Scale score out of 10 (10 = most pain)

Quality of evidence: LOW

- risk of bias in study

| This research provides some indication of the treatment effect.

There is a high possibility that the true effect is smaller or greater. |

References

1)Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis.

2)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

NICE recommends that patients should follow a “healthy, balanced diet”.

There is no randomised controlled trial evidence testing dietary modification to reduce gout flares1,2.

RCTs testing dietary supplements such as vitamin C, cherry or pomegranate extract, or enriched skimmed milk powder were of LOW quality and did not show any effect.

Observational evidence shows that a high BMI and a range of dietary factors are associated with an increased risk of gout attacks:

- excessive meat or seafood consumption

- excessive alcohol (especially beer and spirits)

- sugar-sweetened soft drinks, fructose-containing foods

VERY LOW quality evidence

| This research does not provide a reliable indication of the treatment effect.

There is a very high possibility that the true effect is greater, smaller or absent. |

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

2)Moi JHY, Sriranganathan MK, Edwards CJ, Buchbinder R. Lifestyle interventions for chronic gout. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD010039

3)Singh JA, Reddy SG, Kundukulam J. Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2011 Mar; 23(2): 192-202

NICE makes 2 recommendations1:

1) Offer ULT to those with

- multiple or troublesome flares, tophi or chronic gouty arthritis

- also those with CKD 3-5 or taking diuretic

- these groups have a higher chance of flares, see the Prognosis section below

Large benefits on symptom reduction are described in the Treating to target section below.

2) Discuss the option of ULT with those who

- are experiencing a first flare or who have infrequent flares.

For this second group, there is no direct evidence to guide us.

We don’t know at what point the initiation of ULT will protect these patients from long term consequences of gout.

- Clinical experience shows that long term uncontrolled gout causes joint damage and disability,

- but the value of ULT for those with a new diagnosis or those with infrequent flares is unknown.

Below is a summary of what is known about this. There is no definitive answer, but this may support your understanding and advice to patients.

Likelihood of further flares

more

A study using a UK GP clinical database followed up >20,000 patients after a first attack of gout2. After just under 4 years, the rates of further gout flares* in those not treated with allopurinol were:

| Number of further flares over 4 years | None | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Percentage of patients | 62% | 21% | 9% | 8% |

* Gout flares were defined by a coded entry of gout, accompanied by a prescription for acute treatment

Note: this study probably underestimates the number of flares, missing those not coded properly, or those not presenting at all.

A number of risk factors increased the chance of flares, each one by a few percent only:

- male sex

- younger age

- high BMI

- history of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, CKD

- alcohol use (effect proportional to intake)

- diuretic use*

*This from the NICE evidence review, added here for simplicity

Gout as a progressive crystal deposition disease

more

Gout has been conceptualised as a progressive disease with 4 stages3:

- No disease – asymptomatic with normal urate

- Asymptomatic but with hyperuricaemia and crystal deposition

- Symptomatic with recurrent flares

- Chronic gouty arthritis and tophi

- Symptomatic with recurrent flares

- Asymptomatic but with hyperuricaemia and crystal deposition

The presence of crystal depostion in joints at the asymptomatic stage, and early in the symptomatic stage, has led to the suggestion that early initiation of ULT might be beneficial4,5.

However, this is still only a theoretical idea. The following data illustrate what the current state of knowledge is.

Most people with asymptomatic hyperuricaemia do not develop gout

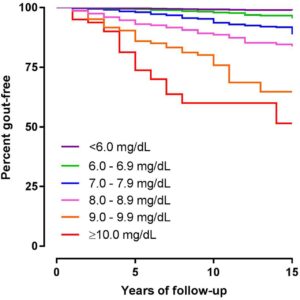

This graph shows how many people remain gout free over 15 years at various levels of hyperuricaemia:

|

|

Reproduced with permission from BMJ Publishing |

|

Unit conversion mg/dL to umol/L: 6 = 356, 7=416, 8=475, 9 = 535, 10=594 |

Source: data combined from 4 prospective health research cohorts, 20186.

How much crystal deposition is there in early disease?

A few ultrasound studies on small numbers of patients with gout of different severities have shown signs of urate deposition in joints.

These are one-off assessments. The implication for those who are asymptomatic or with early disease is not known.

| Characteristics of patients in study | Ultrasound findings |

| 50 patients. Asymptomatic/no joint disease. Mean urate 482umol/L

Recruited from rheumatology, cardiology and nephrology clinics7. |

25% had a DC sign* in an MTP joint |

| 15 patients. Early gout, not on ULT. Mean urate 637umol/L

Mean of 2 gout attacks, 30 months apart. Recruited from rheumatology clinic8. |

40% had a DC sign* in MTP joint 27% had intra-articular tophi in MTP joint |

| 53 patients, longstanding gout. Mean urate 657umol/L

Mean of 15 previous gout attacks over 9 years9. |

67% had a DC sign* in MTP joint 74% had intra-articular tophi in MTP joint |

*DC sign, “double contour” sign. Hyperechoic enhancement of the chondrosynovial interface secondary to the monosodium urate crystal deposition7.

Risk of osteoarthritis

more

Gout and OA share a number of risk factors (most importantly raised BMI) so often occur together.

There is a plausible but not fully proven mechanism whereby urate crystals trigger cartilage degradation10.

There is another plausible mechanism whereby OA precedes gout: damaged cartilage is more likely to trap crystals10.

A 2016 UK GP database study11 found that:

- Patients with a gout diagnosis are 1.45 times more likely to develop OA within 10 years than those without gout.

- Patients with an OA diagnosis are 1.27 times more likely to develop gout within 10 years than those without OA.

-

both figures after correcting for variables

-

Associations with systemic disorders and mortality

more

Gout is associated with cardiovascular disorders, metabolic syndrome, CKD and increased mortality.

However, no causal link has been established – these conditions share many common risk factors3.

Urate lowering therapy has not been shown to reduce adverse outcomes for these conditions or affect mortality12,13.

-

With regard to CKD, 2 small studies on patients with hyperuricaemia and CKD attending renal clinics have shown some slowing of decline in renal function with allopurinol therapy. These are at high risk of bias and this question requires larger long term studies14,15,16.

References

more

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

2)Rothenbacher D, Primatesta P, Ferreira A et al. Frequency and risk factors of gout flares in a large population-based cohort of incident gout. Rheumatology 2011 May; 50(5): 973–981

3)Dalbeth N, Choi HK, Joosten LAB et al. Gout. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5: 69

4)The British Society for Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Rheumatology 2017; 56(7): e1–e20

5)Mallen C, Davenport M, Hui G et al. Improving management of gout in primary care: a new UK management guideline.

6), et al. Relationship between serum urate concentration and clinically evident incident gout: an individual participant data analysis.

7)Pineda C, Amezcua-Guerra LM, Solano C et al. Joint and tendon subclinical involvement suggestive of gouty arthritis in asymptomatic hyperuricemia: an ultrasound controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther 2011; 13: R4

8)Ottaviani S, Allard A, Bardin T et al. An exploratory ultrasound study of early gout. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29: 816-21

9)Ottaviani S, Richette P, Allard A et al. Ultrasonography in gout: a case-control study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012 Jul-Aug; 30(4): 499-504

10)Ma CA, Leung YY. Exploring the Link between Uric Acid and Osteoarthritis. Front Med 2017; 4: 225

11)Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Mallen C et al. Comorbidities in patients with gout prior to and following diagnosis: case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis 2016 Jan; 75(1): 210-7

12)Dalbeth N, Gosling A, Gaffo A, Abhishek A. Gout. The Lancet 2021; 397(10287): 1843-1855

13)Hay CA, Prior JA, Belcher J et al. Mortality in Patients With Gout Treated With Allopurinol: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2021, 73: 1049-1054

14)Effect of Allopurinol in Chronic Kidney Disease Progression and Cardiovascular Risk.

15)Siu YP, Leung KT, Tong MK et al. Use of allopurinol in slowing the progression of renal disease through its ability to lower serum uric acid level. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 47(1): 51-59

16)Roughley M, Sultan AA, Clarson L et al. Risk of chronic kidney disease in patients with gout and the impact of urate lowering therapy: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018; 20: 243

Evidence Source: Various

This is an important question which lacks direct evidence. The NICE recommendations lean heavily on the experience/expertise of the guideline committee.

To find further evidence to unpack this, we drew on a few recent major publications:

- NICE guideline 20221

- British Society of Rheumatology guidelines 20192 and an accompanying BJGP editorial3

- The Lancet. Seminar paper 20214

- Nature Reviews. Disease Primer article 20195

We explored their reference lists as well as conducting informal literature searches.

We have presented a curated summary of evidence which aims to illuminate key areas in this field.

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

2)The British Society for Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout, Rheumatology 2017; 56(7): e1–e20

3)Mallen C, Davenport M, Hui G et al. Improving management of gout in primary care: a new UK management guideline.

4)Dalbeth N, Gosling A, Gaffo A, Abhishek A. Gout. Lancet 2021; 397(10287): 1843-1855

5)Dalbeth N, Choi HK, Joosten LAB et al. Gout. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5: 69

Evidence Quality: HIGH - VERY LOW

Evidence to support ULT in those with recurrent attacks is HIGH QUALITY and detailed in the “Treating to target” section.

Evidence to support introducing ULT for those with milder disease is VERY LOW QUALITY as described above.

Once a decision to take long term urate lowering therapy (ULT) has been made, NICE recommends employing a “treat-to-target” strategy aiming for serum urate level <360umol/L

-

and to consider <300umol/L for those with ongoing flares despite reaching <360umol/L

Evidence for this comes from a pragmatic trial in UK primary care comparing usual GP care with a structured, nurse-led care plan revolving around a treat to target strategy.

In patients experiencing multiple flares per year:

- treat-to-target showed impressive improvements in flare rates and presence of tophi after 2 years

- with few apparent harms

If 100 people like this have a treat-to-target strategy, 16 fewer people will have 2 or more flares per year than those with usual care

If 100 people like this have a treat-to-target strategy, 11 fewer people will have 4 or more flares per year than those with usual care

If 100 people like this have a treat-to-target strategy, 95 will achieve this target urate level compared to 30 of those with usual care

If 100 people like this have a treat-to-target strategy, 8.4 fewer people will have tophi after 2 years than those with usual care

Evidence Source: NICE

Figures derived from the key trial1 in the 2022 NICE guideline.2

Recruited from primary care, 517 patients with established gout and at least 1 flare in the last 12 months were randomised to:

- usual GP care or

- a treat-to-target plan in primary care, including:

- high quality information on gout, consequences and treatments

- structured follow up by clinic visit, phone or home visit by specially trained nurses

- holistic assessment and shared decision making

References

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

2)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

Evidence Quality: HIGH

| This research provides a very good indication of the treatment effect.

However, it is possible that the true effect is slightly smaller or greater. |

NICE rated this evidence as HIGH quality1:

- RCT at low risk of bias

- statistically significant outcomes with reasonable confidence intervals

Reference

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

Study Population

The characteristics of patients in this study1 were:

- mean duration of gout 12 years

- number of gout flares in the previous year:

- 2 or more: 80%

- 4 or more: 36%

- 10 or more: 9%

- mean urate at baseline 440umol/L

- 40% taking allopurinol at baseline

- mean age 63

- 10% female

- mean eGFR 71 ml/min per 1.73m2

- mean BMI 30 kg/m2

- typical range of co-morbidities associated with gout

Reference

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

What happened to urate levels? Which drugs were used?

In the treat-to-target group, the allopurinol dose was increased in 100mg/day increments according to serum urate levels measured every 3-4 weeks.

Urate levels took on average 8 months to reach target

Febuxostat was used as a second line treatment if target was not reached with 900mg allopurinol.

| Usual care | Treat-to-target | |

| Urate at baseline | 438umol/L | 443umol/L |

| Urate at 2 years | 421umol/L | 252umol/L |

| Patients taking ULT at 2 years | 56% | 96% |

| Mean dose of allopurinol at 2 years | 230mg/day | 460mg/day |

| Patients taking allopurinol >300mg day | 10% | 79% |

| Patients taking febuxostat | 3% | 14% |

| Combination therapy | none | none |

| Mean number of gout flares in previous year (at baseline) | 3.8 | 4.2 |

| Mean number of gout flares in year 2 of treatment | 2.4 | 1.5 |

Reference

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

Treatment-related flares in year 1

All urate lowering therapy increases the chance of an acute flare as serum urate levels fall.

- In RCTs of drugs v placebo (see sections below), this manifests as more flares in the treatment groups in the first year of treatment.

In the treat-to-target study, the number of flares in the first year was the same in each group (as treatment-related early flares were balanced out by preventable flares in the under-treated patients).

Patients should be aware that they may experience further flares over the first year while treatment is being titrated.

Reference

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

More about tophi

Tophi actually do shrink (!)

| Diameter of largest tophus (mm) | Usual care | Treat-to-target |

| at baseline | 20 | 17 |

| at 1 year | 17 | 8 |

| at 2 years | 14 | 3 |

Reference

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

For the 255 patients assigned to receive treat-to-target care, the following were reported:

- 12 stopped ULT due to side-effects:

- 4 x rash or pruritis

- 4 x reduced eGFR

- 2 x GI upset

- 2 x arthralgia

- all resolved on stopping therapy

Data on harms was not collected for the usual care group.

Reference

1)Doherty M, Jenkins W, Richardson H et al. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness of nurse-led care involving education and engagement of patients and a treat-to-target urate-lowering strategy versus usual care for gout: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392(10156): 1403-1412

Allopurinol is likely to remain the mainstay of gout prophylaxis.

The NICE evidence review for the 2022 guideline1 and two earlier Cochrane reviews2,3 only found a small number of small, short term trials comparing the two.

- both drugs reduced serum urate

- not enough data on flare frequency to quantify their benefit

- no long term data on tophi, joint damage or risk of OA

The best guide to the effect of these drugs comes from the “Treating to Target” data in the previous section.

NICE recommends either drug as a potential first line treatment, with some points of note in the evidence:

- allopurinol is the most widely used first line drug and was effective at high doses in the “treat-to-target” study above

- febuxostat 80-120mg lowers urate more than 300mg allopurinol, but

- febuxostat has not been compared to higher doses of allopurinol (over 300mg)

- febuxostat may have a greater increase in flare risk in the short term, for example:

- 36 flares per 100 people with febuxostat 80mg, v

- 22 flares per 100 people with allopurinol 300mg within first 3 months of treatment1

- LOW quality evidence

- LOW quality evidence

HARMS

The small, short term trials in this evidence review were not large enough to show any significant harms from either treatment.

See the HARMS data in the “Treating to target” section which details side effects in that study – only 12/255 people stopped meds due to side effects all of which resolved.

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

2)Seth R, Kydd ASR, Buchbinder R et al. Allopurinol for chronic gout. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD006077

3)Tayar JH, Lopez‐Olivo MA, Suarez‐Almazor ME. Febuxostat for treating chronic gout. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD008653

ULT can cause acute flares of gout in the first few months after drug initiation or uptitration.

An option recommended by NICE is to co-prescribe colchicine during drug initiation and uptitration, as prophylaxis against these flares.

- BNF recommends a dose of 500 micograms twice daily for this indication.

- NICE does not specify a duration of treatment. In the key trial, colchicine prophylaxis was continued for 3 months after target urate level had been reached.

- Figure below shows flare reduction when co-prescribing colchicine with allopurinol

- a similar benefit is seen when co-prescribed with febuxostat

NICE also recommends the option of co-prescribing NSAIDs or corticosteroids as an alternative to colchicine where it is not tolerated, though there is no RCT evidence for their use in this role.

If 100 people like this take colchicine for 6 months whilst titrating allopurinol, 45 fewer will experience a gout flare compared to those not taking colchicine

If 100 people like this take colchicine for 6 months whilst titrating allopurinol, 50 fewer will experience two or more gout flares compared to those not taking colchicine

Evidence Source: NICE

Figures derived from a single trial from the 2022 NICE guideline evidence review1.

- RCT included 43 people

- colchicine 600 micrograms bd v placebo in those starting allopurinol prophylaxis

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

Evidence Quality: MODERATE

| This research provides a good indication of the treatment effect.

There is a moderate possibility that the true effect is smaller or greater. |

NICE rated this evidence as MODERATE quality1

- randomised controlled trial, but

- small numbers of patients meaning wide confidence intervals

References

1)National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gout: diagnosis and management 2022 [Internet]. [London]: NICE; 2022. (NICE guideline [NG10151])

Study Population

The population characteristics in these trials were:

- mean age 47-64 years

- almost all male

- baseline urate approx 530umol/L

- low rates of CKD

Patients were being initiated on either allopurinol1 or feboxustat2 as ULT and being treated with colchicine or placebo to prevent ULT-related flares.

References

1)Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis.

2), et al. Stepwise dose increase of febuxostat is comparable with colchicine prophylaxis for the prevention of gout flares during the initial phase of urate-lowering therapy: results from FORTUNE-1, a prospective, multicentre randomised study.

Colchicine was associated with a raised incidence of GI side effects (mainly diarrhoea) in this study:

- 8 in 22 people taking colchicine reported diarrhoea, compared to

- 1 in 21 people taking placebo

Key

People who have an adverse event

People whose adverse event is prevented by treatment

People who were never going to have an adverse event anyway

Graphics and NNTs are rounded to the nearest integer

Stats explained

These three statistical terms offer three different ways of looking at the results of trial data.

ARR

Absolute Risk Reduction

This tells you how many people out of 100 who take a treatment have an adverse event prevented.

MoreThe value of the ARR changes with the baseline risk of the person (or population) taking the treatment. The higher the starting risk, the greater the absolute chance of benefit.

You need to think about over what time the trial data show this benefit, as it is usually assumed that more absolute risk reduction is gained over time.

Your patient might be taking the treatment for much longer than the length of a clinical trial (or, if life expectancy is limited, perhaps for less time).

NNT

Number Needed to Treat

This tells you how many people need to take the treatment in order for one person to avoid an adverse event.

The lower the number, the more effective the treatment.

MoreThe value of the NNT changes with the baseline risk of the person (or population) taking the treatment. The higher the starting risk, the smaller the NNT.

You need to think about over what time the trial data show benefit, as it is usually assumed that more benefit is gained over time and therefore the NNT will drop over time.

Your patient might be taking the treatment for much longer than the length of a clinical trial (or, if life expectancy is limited, perhaps for less time).

RRR

Relative Risk Reduction

This tells you the proportion of adverse events that are avoided if the entire population at risk is treated.

MoreThe value of the RRR is usually constant in people (or populations) at varying degrees of risk.

It is also usually assumed to stay constant over time.

This can be helpful, especially when thinking about population outcomes, but can be misleading for an individual person:

For example, a RRR of 25% in someone with a baseline risk of 40% would give them an ARR of 10% and an NNT of 10.

A RRR of 25% in someone with a baseline risk of 4% would give them an ARR or 1% and an NNT of 100.